Updated: August, 2022

© 2022 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Check out our free webinar on the Social Competency Model.

The social world is vast and filled with countless social landscapes; it becomes increasingly nuanced and complex as we age. From the time we are babies and throughout our lives we are observers and participants in what's happening around us and through different types of media. Each of us is expected to intuitively learn (to varying degrees) about the social world through movies, news, literature, history and during face-to-face and online experiences with people we know and even those we don’t.

We usually take one another’s social skills for granted because of the ease in which most of us learn to produce them—usually without direct instruction. In fact, we rarely notice each other’s socially based proficiencies or social competencies, but we are fairly quick to notice if someone’s social responses aren’t quite on point within a specific situation.

The neurotypically developing brain learns over time to be a super-sensitive detector to what others are doing, saying, thinking, planning, and feeling in the social world. As children age, most also become adept at simultaneously trying to figure out how others may be thinking and feeling. Our mind is designed to actively process social information to figure out how the social world works and how each of us can work better within that world. We are expected to employ this social information thinking process whenever we interact or share space with others. Common scenarios include when we share space with others, when working with a team, and when spending time with family or friends. We also do this to understand how and why someone is feeling and/or thinking a certain way, and to help us decipher meaning and the hidden social rules associated with any text we may be reading, people we are watching on screens, etc.

The Social-Academic Connection

Students are expected to use social information processing through the school day as they are surrounded by people, some of whom they like, some they may not like, etc. Students also use social information processing within their curriculum, although this comes as a surprise to many administrators, teachers, and parents. While most think the social mind is relegated to the playground and after school activities, schools around the world depend on academic standards (educational benchmarks) to guide what they teach students of all ages. Many aspects of academic curriculum have standards/benchmarks with socially based information processing embedded across subjects such as language arts, social studies, history, civics, science labs, etc. Any standard/benchmark that focuses on concepts such as point of view, expressing oneself clearly, describing context, characters, traits, motivations, use of feeling words, making inferences, thinking critically about the relationships, collaboration, teamwork, etc., all have a foundation of thinking socially. To illustrate this, three academic standards are listed below. The bolded words demonstrate the ways in which we expect students to bring their knowledge of how the social world works into their academic learning.

Sample Academic Standards:

- Kindergarten Speaking and Listening: Follow agreed-upon rules for discussions (e.g., listening to others and taking turns speaking about the topics and texts under discussion).

- 3rd Grade Reading Comprehension: Describe characters in a story (e.g., their traits, motivations, or feelings) and explain how their actions contribute to the sequence of events.

- 7th Grade Written Language: Engage and orient the reader by establishing a context and point of view and introducing a narrator and/or character; organize an event sequence that unfolds naturally and logically.

Most people view social skills as how an individual is behaving, playing, and interacting; they teach from the point of view that all social behavior occurs during social interactions. Many do not realize their students need to interpret social information prior to producing relevant and related social responses. Yet, our more sophisticated, highly verbal students need to be taught explicit information to help them understand how the social world works for them to better understand how to navigate to regulate in the social world. Think of these as "essential ingredients" for their deeper learning to generalize what they are learning across different landscapes in their social world and to handle expanding social expectations as they age.

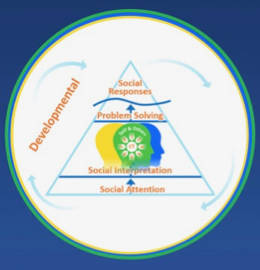

The Social Thinking-Social Competency Model (SCM)

The goal of the Social Thinking® Methodology is to take complicated social learning processes and teach them explicitly in a way that social learners of all ages—and interventionists—can understand. Over the several decades since the Social Thinking Methodology was introduced in the mid-1990s, our work has been and continues to be, informed by many bodies of research and theory. These include, but are not limited to, social learning theory, social information processing, perspective taking, self-regulation, executive functioning, communication, autism, ADHD, sensory processing, reading comprehension, written expression, managing complex behavior, etc.

Ultimately, it became clear that the focus of our work is to teach students social competencies, which is much more than social skills or teaching students to “behave!” Through this process of integrating well-established research studies, including research on social information processing (Crick and Dodge, 1994; Beauchamp and Anderson, 2010) and thought into our methodology, we were inspired to develop the Social Thinking®–Social Competency Model.

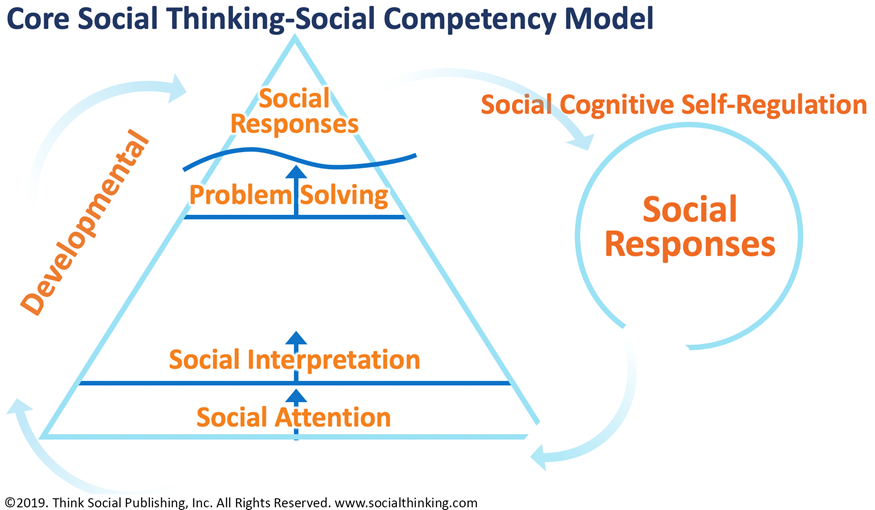

Image 1

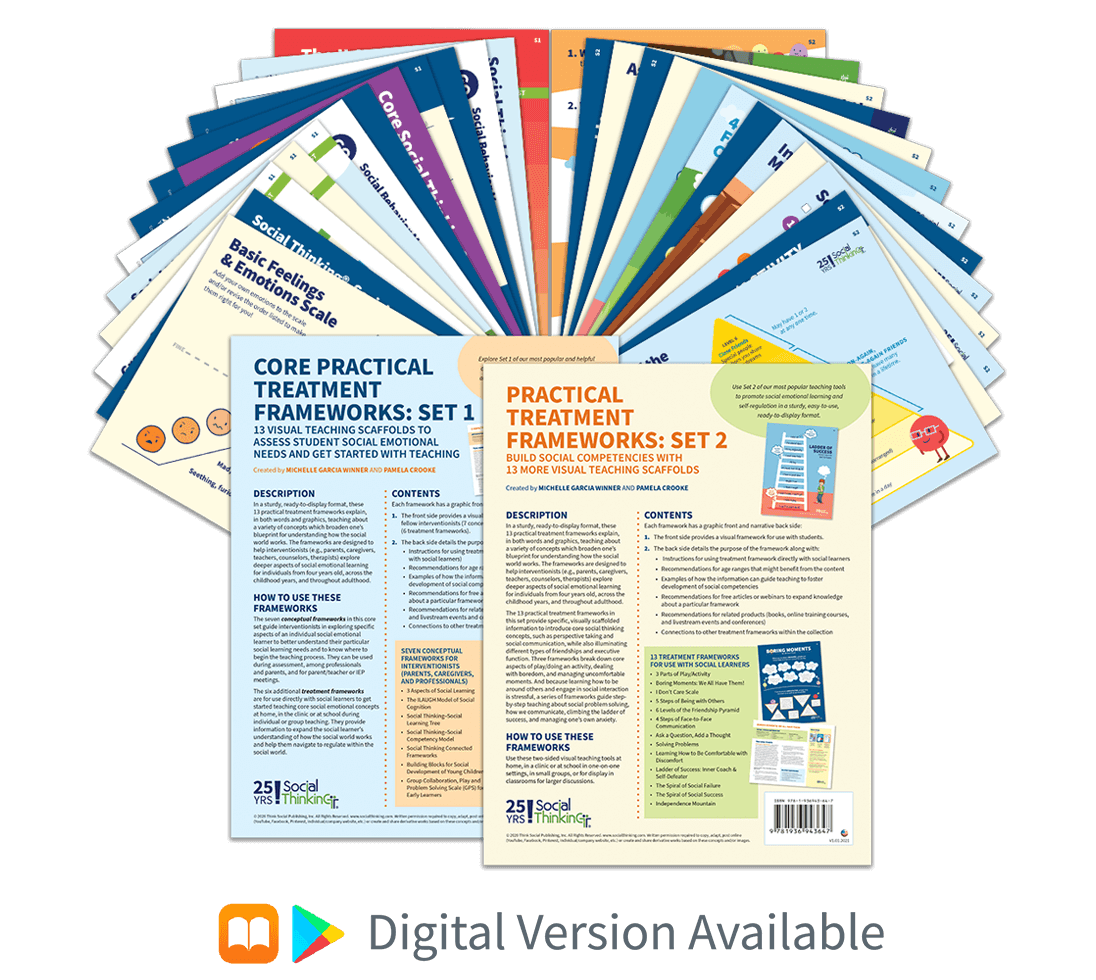

The best way to think about this model is to imagine an iceberg. The swoop on the graphic represents a waterline. What we see above the waterline can be thought of as the social behaviors we notice in one another. We refer to these as social behaviors or social responses rather than “social skills.” The area below the waterline represents the building blocks of one’s social competencies (Image 1). The ST-SCM has four distinct parts, three of which fall below the waterline: Social Attention, Social Interpretation, and Problem Solving as illustrated in Image 2. Our social competencies continually evolve across our lifetime; they are described as “developmental.”

Image 2

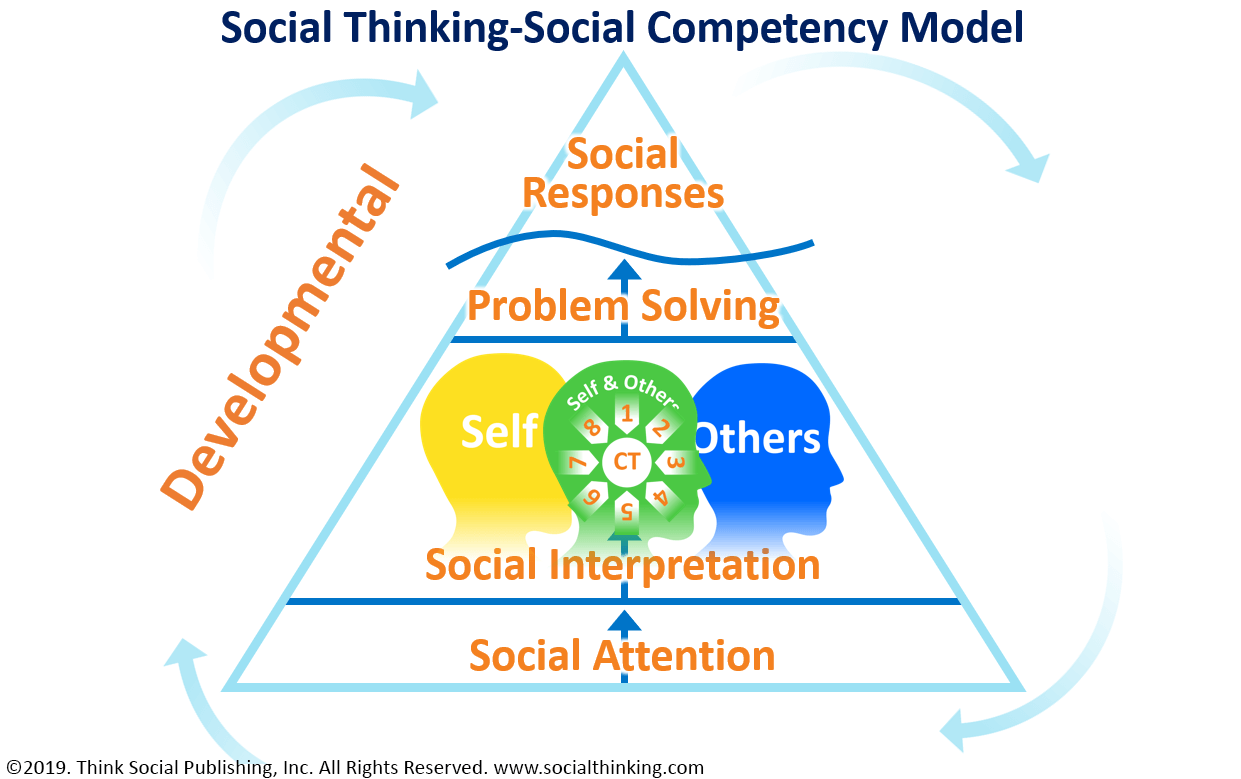

Social Attention refers to how one attends to others in specific situations and contexts. Without social attention, students would not be able to figure out what’s happening around them in the classroom or on the playground (the situation) to understand how to function as part of a group, etc. Because most children have spent years attending to and interpreting the social world prior to coming to school, their social minds are primed for reading comprehension within written text. To that end, from their early school years students are expected to describe “the setting” of a novel or story book as well as naturally infer how the setting connects to what may be happening with the characters in that setting.

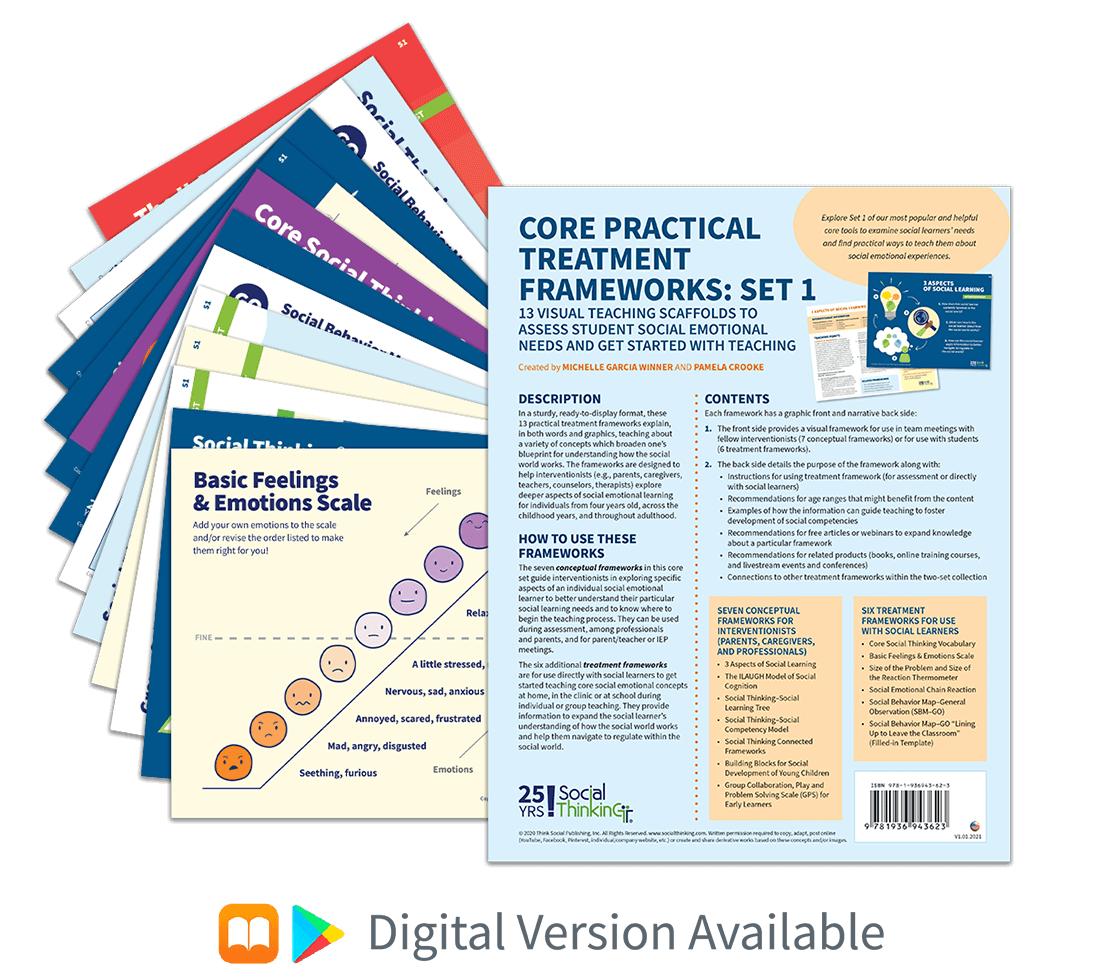

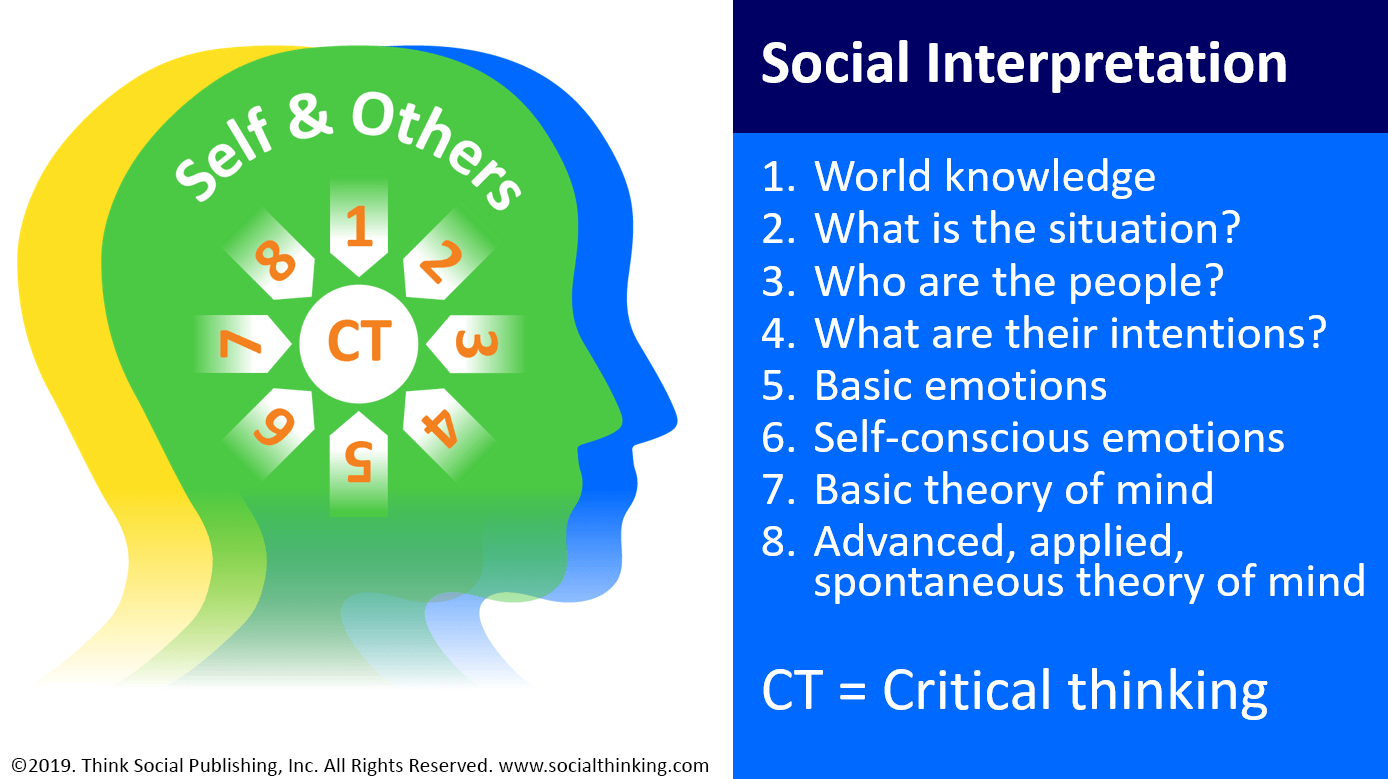

Image 3

Social Interpretation is developmentally, socially, and neurologically miraculous. In neurotypically developing children it occurs when an individual’s brain attends to interpret socially based information. As mentioned previously, social interpretation is more than making inferences; it involves understanding self and others to make sense of people’s information, plans, intentions, even humor! To interpret well is to understand that each of us has unique thoughts and feelings while we share information, plans and goals. Research in early child development teaches us that from a very young age, children are considering what others might be thinking and feeling as part of what they are thinking and feeling (Tomasello, 2009). This is referred to as "self-otherness", "we thinking" or "we cooperation." This helps us interpret self and others as well as our self with others throughout all aspects of the social world as illustrated in Image 3. It also helps us cooperate and learn in groups, our families, and communities—including the classroom and school!

Social interpretation involves many moving and shifting parts, all of which require simultaneous and synergistic interaction as illustrated in Image 4. These parts include, but are not limited to:

Image 4

Aspects of Social Interpretation:

- World knowledge: incorporating information based on our learning from experience

- What is the situation? What’s going on at this particular moment?

- Who are the people? What is known about me and them; each person’s role, our social memory, etc.

- What are your and other people’s plans and intentions in this situation based on the people?

- What are you and other people thinking, wanting, etc.? (basic perspective taking/theory of mind)

- What do you or other people need to consider in the moment of a social interaction or when sharing space? (advanced perspective taking/spontaneous theory of mind)

- How do you and other people feel in the situation? (basic emotions)

- How do you and other people feel in comparison to others? (self-conscious emotions)

Individuals who are actively developing their social interpretation skills are engaging in basic socially based critical thinking starting at about age three. Robust critical thinking is embedded in students' curricula (around the world) by the age of nine, if not sooner. Furthermore, we expect each person’s critical thinking and interpretive abilities to continue to progress throughout the rest of their lives!

Problem Solving—socially based problem solving to be precise--emerges from our ability to attend to and interpret relevant social information. When we problem solve, we consider many different variables (e.g., the potential problem, different points of view, our desired goal, the choices we have to accomplish the goal, the consequences of each of the choices, etc.).

One doesn’t need a large "problem" to engage in this process. Virtually every aspect of our social responses (which we refer to as Social Cognitive Self-Regulation) is determined through a problem-solving approach. Consider these examples:

- Should I say hi to that person?

- Should I raise my hand to speak in class?

- Is my topic sentence clear?

- If I say _____ will I offend that person?

- What part of my story should I tell and, what part can I leave out because they already know?

Ultimately, the problem-solving process encourages us to make decisions about which social responses will result in meeting our social goals, whether the goal is to relate well with another person, share space effectively without intruding or make others feel uncomfortable, or figure out what other people may be thinking or feeling, etc. Problem solving can help us work through a small dilemma or a major crisis; it provides the information from which we can decide which actions to take to navigate and regulate toward our optimal social response.

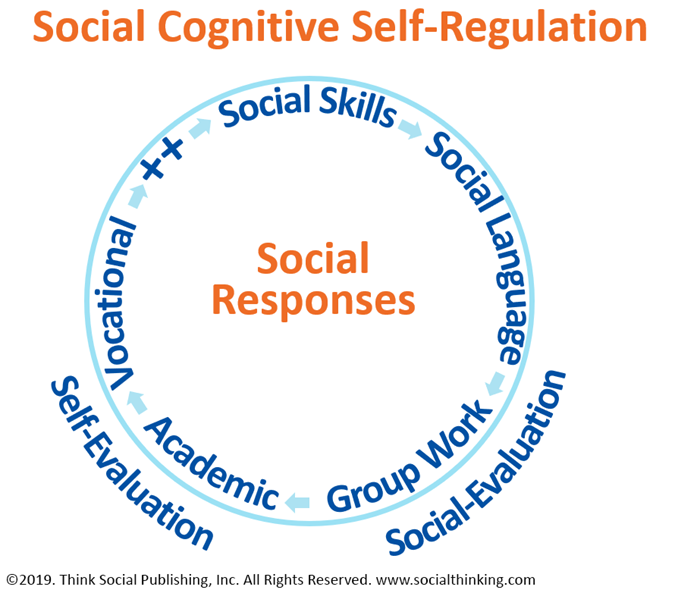

In Image 2, problem solving sits just below the waterline. It's positioned here because, while problem solving to make decisions is a cognitive process and is usually invisible but social responses are perceived by others. This leads us above the waterline to social cognitive self-regulation as illustrated in Image 5. Social Responses refer to not just one thing (behavior) but several things working in tandem. Together this is called social cognitive self-regulation.

In Image 5 you will also notice two other terms below the circle: self-evaluation and social evaluation. Social-evaluation refers to our constant awareness of the situation and the people. Social landscapes can change quickly and may require us to rapidly alter our social response. Self-evaluation refers to our self-awareness, problem solving and social response management based on how we feel we are doing in a specific situation. Social-evaluation and self-evaluation are ongoing processes that are at the heart of developing and managing our social competencies.

Socially based problem solving leads us to determine our social responses and is an important part of self-regulation. Social cognitive self-regulation involves social responses that appear quite simple to most (e.g., walking around people as you pass them on a sidewalk, or greeting) as well as social responses that require layers of social competencies (e.g., engaging in a face-to-face group discussion; sharing your point of view that is different from that of your conversational partner, etc.). Social cognitive self-regulation is the process through which you figure out how to respond to another person, whether that person is a friend or stranger.

Image 5 also shows different types of social behaviors, including nonverbal social behaviors (facial expressions, gestures, touch, body stance/orientation, silence, ignoring, etc.) and verbal responses (concrete and figurative language, tone of voice, pace of our speaking, etc.). We choose our social behavior(s) by considering how our words affect the possible way others might interpret our actions. We also use and/or modify our social responses differently in different contexts. (e.g., building a friendship, working in peer groups in school, working on a team as an employee, working collaboratively with people in our community/team/place of worship, etc.).

Image 5

What is emotional self-regulation?

People often describe emotional self-regulation as managing their stronger social responses, usually when they are experiencing strong (negative) emotions. This process involves the same steps outlined in the ST-SCM. During the interpretation step, we are trying to understand our own and perhaps others' feelings. Ideally, individuals make decisions to utilize social responses that will help them achieve their desired social goal if it is not likely to cause additional problems for self or others. The bottom line is that social cognitive and emotional self-regulation are not mutually distinct.

Group-based social cognitive self-regulation

Social cognitive self-regulation in a classroom involves many people attempting to self-regulate simultaneously. This can include conflicting opinions about what is important to each person at any one time. For this reason, classroom management can be difficult! It can be helpful for interventionists to work with students and engage in active conversations to explore their shared goals within the class. Remarkably, most of our social goals are not those we talk about, but instead are the goals we simply expect from each other.

Building social competencies is an ongoing process

The core of the ST-STM is to illuminate the process through which we all form social responses tied to each situation’s (often unstated) social norms. The ST-SCM represents a continuous and persistently cyclical process as we move from situation to situation throughout our day. Even when we are not actively engaging with our environment (think about a student waiting for her ride at the end of a school day), we are still going through this social processing to figure out what to do next in the situation. Most importantly, we want interventionists to understand that each part of the ST-STM—attend, interpret, and problem solve to decide the social responses to produce—represents social competencies for our students to learn, use, and build on throughout their lives.

The ST-SCM is developmental

A five-year-old's social competencies are not as sophisticated as those of an eight-year-old, and a 21-year-old needs more sophisticated social competencies than a 14-year-old. The general expectation, across cultures, is that our social competencies will continue to evolve through our own personal, social emotional learning processes throughout our lives. This idea is demonstrated by the fact that as people become senior members within societies around the world, we refer to them as “wise.” We attribute this evolved sense of social know-how to age and the assumption that, as we age, we go through many more experiences that build our social competencies. Note: CEOs are now recognizing the importance of social competencies in the workforce and are recommending that high schools and universities incorporate courses that talk about and teach these skills.

Different social learning trajectories

Not everyone develops social competencies in the same manner, on the same timeframe, or to the same level over time. Social learning is based on the neurology we were born with and/or changes to our neurology from trauma, illness, addiction, etc. Just as people experience learning differences or disabilities in math, reading or science, some people also experience learning differences or disabilities in social emotional learning. The Social Thinking Methodology takes into account these individual differences and has components to teach individuals of varying abilities: both Neurodivergent and neurotypical. Unlike programs that "teach to mastery" or assume an "end" to a social skills program, interventionists use the Social Thinking Methodology to encourage individuals’ improvement in social competencies compared to their unique baseline learning abilities. Social learning should be a constant throughout each of our lives.

Managing our social mind requires a systematic approach

Our ability to engage in social learning on our pathway toward social cognitive self-regulation can be hampered by factors that overwhelm our ability to stay present, focused, and able to process relevant social information. Using our social competencies also involves at least three other major factors that are internal and external to our being:

- Sensory processing

- Anxiety, sadness, emotional trauma, etc.

- Screen Time Overload on Portable devices (STOP)

Each of these three variables is represented on the extended ST-SCM with line that surrounds the ST-SCM as shown in Image 6. Sensory processing is noted by the solid light blue line. The dotted blue line represents emotional experiences related to anxiety, sadness, trauma, etc. and the solid green line signifies the challenges students have paying attention in their face-to-face social world when their attention is swallowed up by screen time on their portable digital devices.

Image 6

Sensory processing and social competencies

A person whose sensory system is flooded by physical sensations (sights, sounds, smells, etc.) that overwhelm will likely find it difficult to learn about and/or engage their social competencies. Interventionists should be aware that sensory overwhelm impacts one’s social learning capabilities. Sensory issues vary from individual to individual; what may be overwhelming to one student may not even affect another. Occupational therapists are highly skilled in assessing and helping students learn strategies to manage their sensory processing while simultaneously learning to manage other demands, whether they be social, academic, leisure, etc.

Learning to manage stressors

Stressors such as anxiety, sadness, depression, prior or current trauma also influence our students' abilities to attend, interpret, problem solve to decide how to respond to meet their social goals. For some, the stress of not fitting in and being excluded by their peers may cause anxiety or sadness. Some individuals may develop social anxiety for unknown reasons. Others find they are hypersensitive to how people treat them, because of a personal history of trauma, including bullying. Stressors dull one’s ability to focus on social information processing; for some, especially tweens and teens, this may result in an "I don't care" attitude toward being with peers or cooperating with authority. The social world can induce many stressors. Learning to manage stressors such as anxiety and depression associated with complex social experiences and confusing feelings is a key step in developing and utilizing social competencies. The dotted blue line surrounding the ST-STM represents our ongoing work to help individuals develop strategies to manage stressors (current or prior) while they are learning social competencies.

Screen Time Overload on Portable devices (STOP)

Another compelling factor influencing the development of social competencies is the emergence and popularity of portable digital devices. In today's digital world, we are all surrounded by digital devices that are in constant competition for our social attention. These devices often become a replacement for the face-to-face social interactions we would otherwise be engaging in—such as hanging out with friends, asking others for help or advice, or developing new face-to-face relationships. It is the face-to-face interactions that foster the development of social competencies As a result, more and more people find it difficult to figure out when to socially attend to the broader social landscapes in their world versus when to attend to what appears on their portable digital screen.

To complicate this point, many school districts have adopted digital devices for all students. While at face value this may seem positive, teachers report growing challenges in getting their students to engage in groups and teaching time when there is digital competition. Students find their way to websites that are more fun, more interesting, more engaging than doing the assignment, or listening to the teacher talk, or engaging in group interactions. Yet, without practice in face-to-face interactions, with its twists and turns that require students to think quickly and flexibly, they are missing out on opportunities to engage in social information processing and practice core social competencies.

This digital competition for attention clearly has an impact on the social learner as it blocks engagement beginning with the most basic social competency: social attention. As we mentioned earlier, if students can't (or don't) attend socially, they will struggle to interpret a situation, problem solve it, or figure out a response. Eyes focused on a screen are eyes missing social clues and cues from the environment. Brains focused on a screen are brains that are missing out on opportunities to engage in the constantly changing social world.

Summary

The social mind has evolved to allow humans to process and respond to complex emotions and to consider and interpret the thoughts of self and others on a life-long journey toward problem solving and social cognitive self-regulation to reach our social goals—as individuals, as groups, as cultures and societies. The social world provides endless opportunities for interpreting and responding to social information through both face-to-face and digital experiences, through books, movies, television, and the internet. But the social mind also requires us to manage factors that compete for our face-to-face social attention (sensory processing, mental health related stressors, and screen time overload). To foster social learning and group engagement is to help individuals learn to manage many factors within their internal and external worlds. Our goal, as interventionists, is to help our students learn not just academics, but also the social competencies that will aid them in becoming increasingly successful in the social world throughout their lives. The Social Thinking Methodology continues to evolve so that as our world changes, so do the frameworks, strategies, and materials we produce to help students learn explicitly how to engage in social information processing, how to attend, interpret, problem solve and respond in any situation.

Explore our many free articles and webinars, in addition to our core information for interventionists and developmentally based teaching concepts and strategies for individuals of different ages. Just as each of our social minds continues to expand over our lifetime, so too does the Social Thinking Methodology expand to meet your changing needs.

References

Beauchamp, M. H., & Anderson, V. (2010). SOCIAL: an integrative framework for the development of social skills. Psychological Bulletin, 136 (1), 39.

Crick, N.R. & Dodge K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanism in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115 (1), 74-101.

Kuypers, L. (2011). The zones of regulation. Santa Clara, CA: Think Social Publishing, Inc.

Tomasello, M. (2009). Why we cooperate. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.