© 2021 Think Social Publishing, Inc.

We all encounter problems routinely. Some of them are caused by our own mistakes, such as sleeping through the alarm or missing a meeting. Some are caused by others, (a stolen wallet) and some are just bad luck (getting stuck in a traffic jam)!

Just about everything we do throughout the day involves solving some kind of problem; it’s just an unavoidable fact of life. What we can do, however, is learn to manage our problems. This involves, in part, managing the emotions that arise when a problem occurs. It also involves being aware of the effect our reactions to our problems have on ourselves and others.

Our ability to regulate our emotions in problem situations greatly influences how effectively we are able to solve the problems we face. In fact, emotional regulation is frequently the determining factor in whether or not the problem is solved and how easy or difficult it is to do so. For example, when a problem occurs, most of us are able to quickly figure out the size of the problem and then regulate our emotional reaction to stay calm and able to deal with it. But that’s not always the case. New or even bigger problems are created when the size of our reaction is mismatched to the size of the actual problem. Who wants that?

Defining Socially-Based Problems

Einstein once said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem I'd spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” He had a point! When a problem occurs, many of us just swoop in and start trying to solve it without fully understanding what happened. We may overreact or shut down emotionally, making us unavailable to solve the problem at all. This wastes time and energy and often results in the creation of new or bigger problems.

Defining a social problem may include:

- Understanding the stated or hidden social rules—what’s expected in any given situation. As long as everyone follows the hidden rules and is doing what’s expected, there is no problem and everyone feels okay.

- Understanding the reactions of others, especially when our behavior is unexpected

- Understanding the perspectives and emotions of others.

Conflict can arise when someone has a very different point of view or interpretation of the “rules” in the situation. For instance, we recently worked with a student who became really upset by a teacher’s perspective as he had a very different point of view. While the teacher considered the student’s behavior “unexpected”, the student felt it was fully “expected” based on his point of view. This is why, when working with our students with social learning challenges, it’s so important to spend time first defining the actual problem from multiple people’s perspectives. That way all people recognize what the actual socially-based problem is! (Ross Greene, creator of the Collaborative & Proactive Solutions model, addresses this topic in detail. Learn more at www.livesinthebalance.org.)

A Problem-Solving Equation

It is helpful for our kids to learn formulas, equations, and frameworks to organize their own thinking. We find the following formula pretty helpful:

A socially-based problem =

an unexpected event or perspective + an uncomfortable feeling

It should be noted that not every unexpected event is a problem. Some unexpected events cause us to feel happy or excited: flowers being delivered, hitting all green lights on a busy street, etc. These situations do not become problems because of the positive emotions associated with them. This is why we add an “uncomfortable feeling” into the formula/equation.

This problem solving equation was created with a group of middle school boys who wanted an easier way to talk about problems and how to solve them. Through our collaborative effort, we discovered that our feelings of discomfort, anger, and/or stress are what motivate us to solve the socially-based problems we face, simply because of our basic desire to feel better. When we feel more comfortable with the situation, we can move on with our plans. In fact, the ultimate goal in social problem solving is to achieve the highest possible level of emotional comfort for everyone involved. Think about it.

The Size of a Problem

Problems are not created equal. For children they can be as commonplace as a paper cut or as complicated as having to cope with a family tragedy. When working with our socially-challenged kids we talk about problems in three sizes: small problems, medium problems, and big problems. Regardless of scale, the hidden rule in problem solving with preschool and elementary school age children is that we are expected to react to problems in a manner that matches (or is smaller than) the size of the problem. This is where social problem solving can get tricky. A problem that is perceived by one person as being small could cause a person with social learning challenges to have big feelings about it and then have a big reaction, which would be unexpected. Not only does this mismatch create more anxiety in the individual, it can also limit the effectiveness of solving the current problem while at the same time creating a new problem.

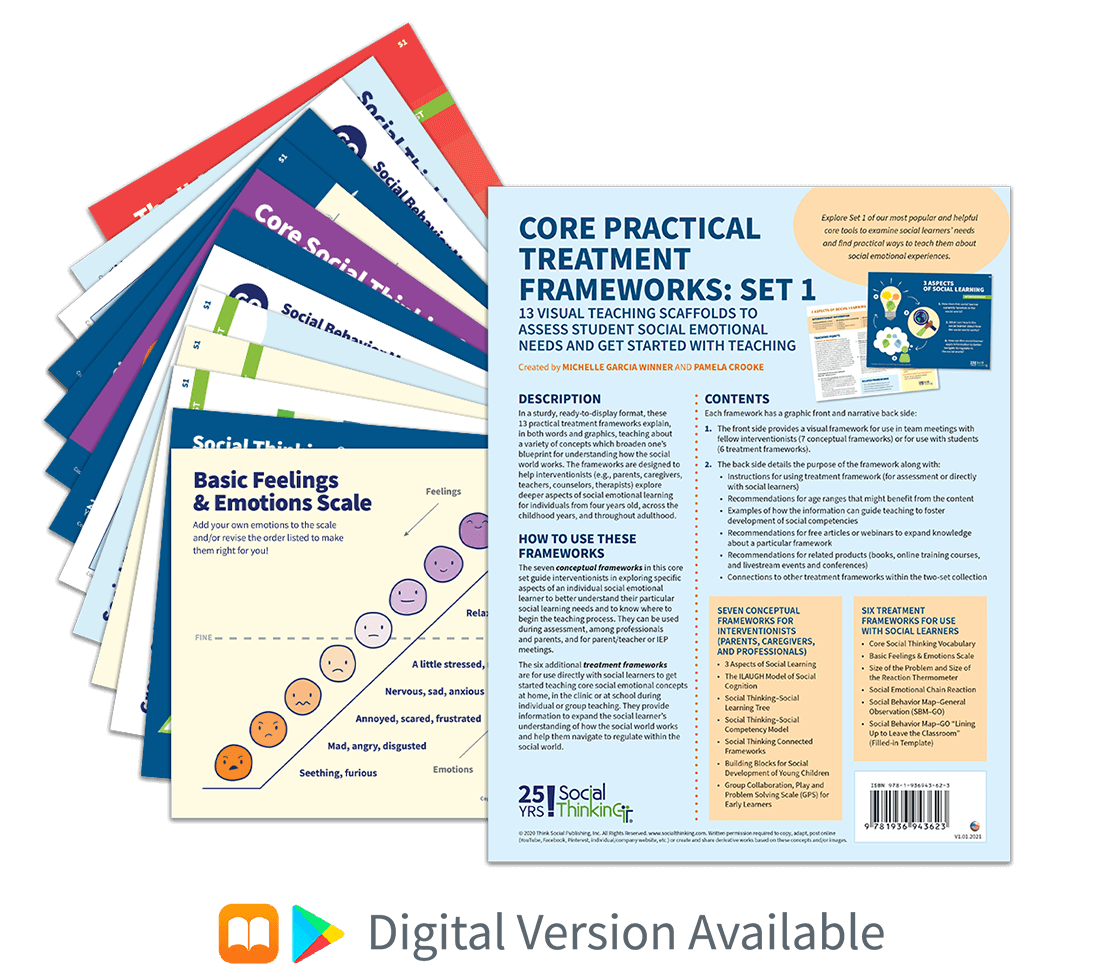

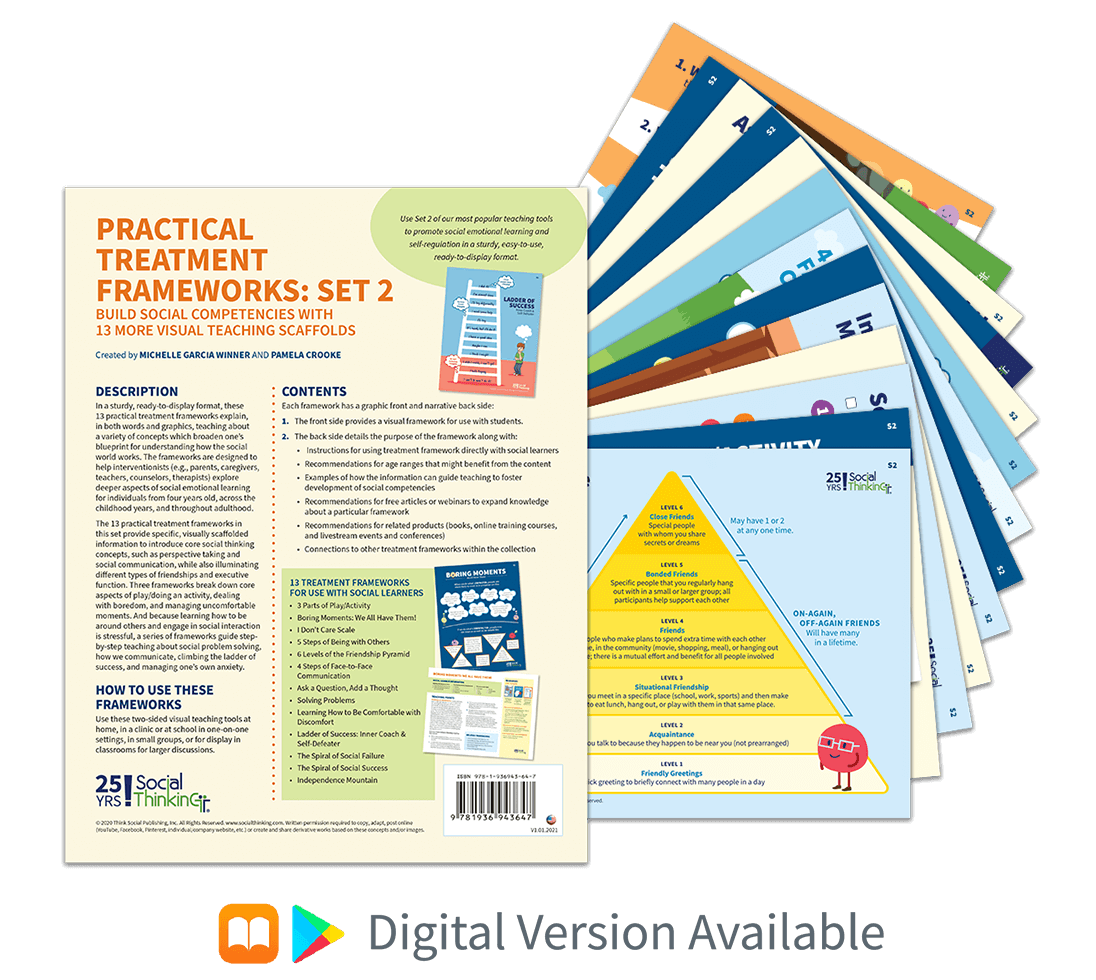

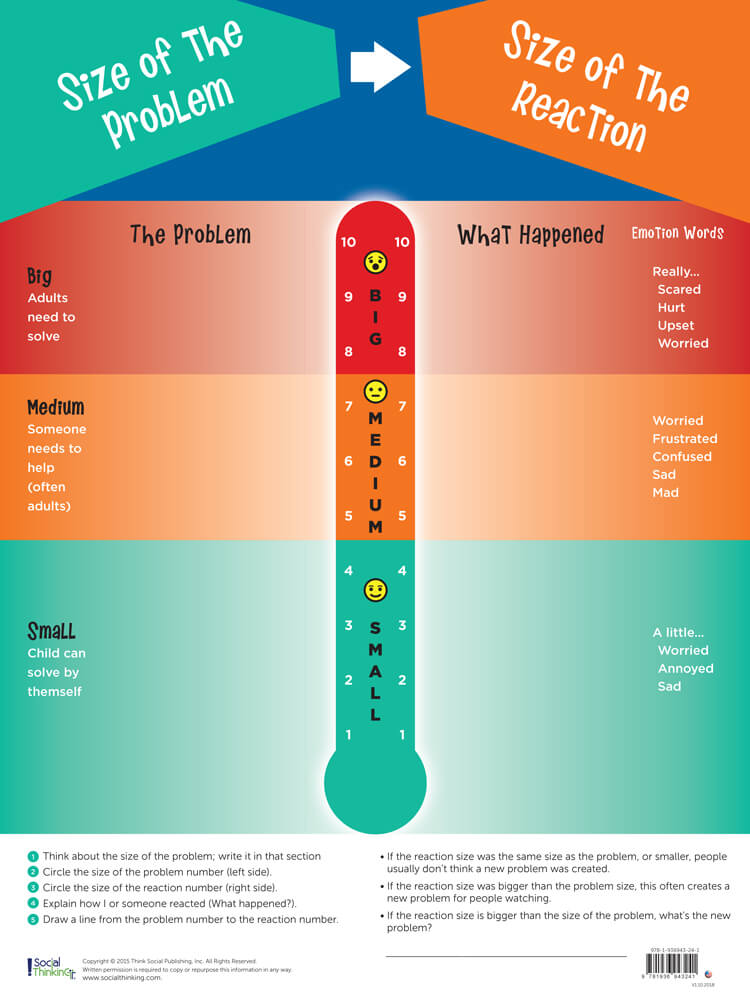

Figuring out the size of the problem is the first step in being able to match our emotional reaction accordingly. The team at Social Thinking has created a poster that helps develop our student’s awareness of the process of matching or minimizing the size of our reaction to the size of the problem.

The thermometer has the numbers 1-10 ascending from the bottom to the top. The numbers 1-4 represent small problems. Small Problems are defined as those that can be pretty easily solved on our own, despite us possibly feeling a little sad, annoyed, or worried. For instance: having to sharpen a pencil point that broke, doing homework even when we don’t want to, or forgetting they were supposed to bring something to a friend.

Medium problems fall into the 5-7 range. They require

someone’s help, often an adult, to solve. That said, it is expected that

kids help solve medium problems. Some examples include figuring out a

math problem, getting a ride to the store for a project, or forgetting

their lunch at home. Medium problems often make us feel some degree of

mad, sad, confused, frustrated, or worried.

The numbers 8-10 represent big problems. A big problem makes us feel really scared, hurt, worried, or upset. Big problems are solved by an adult. For instance: being bullied, getting very sick or injured, or dealing with unfortunate events outside of our direct control. Even adults usually need help solving big problems!

Helping our students learn to recognize the size of their problem and examining the related size of their emotional reaction is an important part of teaching social problem solving. Our poster can help encourage this process.

Start by having students write their problems on the poster in the green, orange, or red sections and circling the corresponding number on the left side. This represents what they think is the size of their problem. Next, they write their reaction (or the desired reaction) on the right side, next to its corresponding number. The student then draws a line from the problem number to the reaction number. If the size of the reaction is the same size as the problem, or smaller, we teach that people usually don’t think a new problem has been created. If the reaction size was bigger than the problem size (the line goes “up”), that’s unexpected and a new problem has been created. The student then describes what the new problem may be at the bottom of the poster.

For example, when struggling to get their homework done students often perceive homework as being a small, or perhaps medium–sized, problem. In this situation students will seek help from their peers, parents or teacher while showing some mild level of frustration; the student’s emotional reaction fits the problem. Help is given, the student calms a bit more, and the problem gets solved. Other students, however, react to their difficulty with homework by throwing their pencil on the floor, arguing with the teacher/parent, or refusing to do it altogether. Not only does the problem remain unsolved, the larger reaction both limits the child’s ability to consider a proactive solution and creates a new problem: increased anxiety and discomfort in those around the student. Furthermore, the adult who could have been there to offer homework assistance is now faced with trying to manage the fall-out from the student’s large emotional reaction.

Stop and Think about Feelings versus Emotions

Students with difficulties with executive functioning are highly prone to have problems regulating their emotional reactions. Let’s teach kids to take the time to Stop and Think as part of learning self-control.

We also want them to learn that we all have feelings and our feelings are okay. “Feelings” are what we feel regardless of whether we have language to describe them. One the other hand, “emotions” are words we use to label how we feel so we can create a better cognitive awareness and begin to learn the process of emotional self-control.

We cannot change our feelings but we can help our students understand how to control the size of their emotions. As they learn to stop and think, they can begin to learn that not all problems are big problems and by better understanding their emotions, they can also possibly change their emotional reaction size in relation to the problem.

Teaching our students that different sized emotional reactions are expected for different size problems helps our students find logic in a sea of emotion. On the other hand, many of our students have impulse control issues and get flooded by big feelings to something even they might agree is a fairly small problem. They have not yet learned to control their emotions. Once again we try to infuse logic: when a big emotional reaction is produced in response to a medium or small problem, other people get upset. This results in new problems for all people involved, including the student.

Points and discussion items at the bottom of the poster help the teacher/parent work with students to determine if their emotional reaction kept other problems at bay, or whether a new problem was created.

This information will take time and effort for your student to learn. Encourage small steps of improvement. Helping your students use language to describe the size of their problem and the expected size of their emotional reaction helps them develop their own level of self-awareness. Allowing them time to stop and think through this process teaches we all take time for self-control; this is all part of the social learning process.

My friend Sal could have used these lessons years ago, but ultimately he got it. Sal consistently overreacted to a variety of situations. One day in middle school, he spilled ketchup on his new shirt at lunch and cried and yelled at a kid who gave him a napkin to clean it off. The kid walked away and Sal spent the rest of the day in despair, wondering why no one would talk to him about it. We spent months teaching Sal how to match the size of his reaction to the size of the problem. Despite being able to verbally explain the process, Sal continued to react in big ways to small problems until one day when Sal broke his arm in gym class. This event, in most of our lives, warrants a big reaction. As expected, Sal cried and yelled, but instead of people moving away like they did in the ketchup incident, people moved toward him to help. This prompted Sal to actually calm down and “work the problem” with them to get him to the doctor as quickly as possible.

When Sal returned to school the next week, we pulled out the poster and he wrote “spilling ketchup” next to the number 2 (small problem) on the left side of the poster and “cried and yelled” next to the number 8 (big reaction) on the right side of the poster. Next, he drew a line from the 2 to the 8 and was able to explain how his reaction did not match the size of the problem and actually caused a new problem. He described his problem like this, “If I stay calm, people care, if I freak out, people stare.” Priceless!

Sal was able to see how crying and yelling was expected and matched the size of the problem when he broke his arm but it worked against him when he spilled the ketchup on his shirt.

This was a turning point in Sal’s ability to recognize the actual size of a variety of problems and his newfound awareness prompted an improvement in adjusting his reaction accordingly. Sal’s story is also a good reminder to all of us: when teaching students about problem solving, it is also helpful to encourage students to explore that people are more similar than different in how they think and feel about the social expectations and related emotional responses that surround them.

Matching the size of our reactions to the size of our problems takes time, learning, and repetition to master. But with practice we can help our students better understand the importance of doing this to help them feel calmer, enjoy the support of teachers and peers, and avoid creating new problems! Stop and think about it!

BIOS

Beckham Linton is a member of the Social Thinking Training and Speakers’ Collaborative, a team of professionals hand-picked by Michelle Garcia Winner who work directly with clients and also provide day-long and shorter customized training on Social Thinking and social learning. Read Beckham’s complete bio here.

Michelle Garcia Winner is the creator of the Social Thinking methodology and founder/CEO of Social Thinking. A prolific writer and international speaker, she specializes in the treatment of individuals with social learning challenges at the Social Thinking Center, her clinic in San Jose, California. Michelle helps educators, mental health professionals, and parents appreciate how social thinking and social skills are integral to a person’s success – be it in school, in relationships, in the community, or in their career.